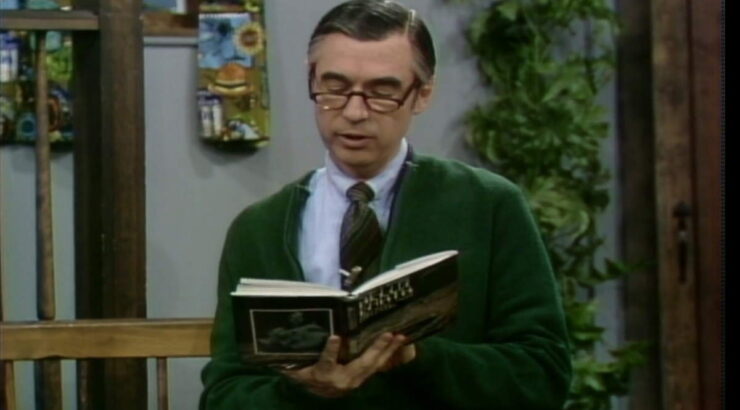

After more than forty years, I still maintain that the greatest moment in the history of television took place on February 6, 1980. That day, in episode #1468 of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Fred Rogers famously visited the set of The Incredible Hulk, devoting nearly an entire episode to the artistry, the science, and the people who made the show come to life. Even in our age of pop culture crossovers, I wonder if anything could top Mister Rogers sitting with a shirtless Lou Ferrigno while he puts on his green makeup, asking, “What do you do when you get angry?”

Like many members of my generation, I looked up to Mister Rogers as if he were an extra parent. Moments such as his appearance on Hulk remind me that Fred Rogers’ exploration of “make-believe” not only helped children to grow up, but also cultivated a love of storytelling, planting the seeds for creativity and experimentation. Every week, Mister Rogers challenged his viewers to ask questions, to build their empathy, and to be unafraid of failure.

Try rewatching a few episodes and you’ll pick up more than a few lessons, including:

Learn How It’s Done

Perhaps the most beloved aspect of Mister Rogers’ show was his willingness to pull back the curtain on how everyday things were made, from crayons to peanut butter. His visit to the set of Hulk was no different, as he aimed to show his young viewers how a team of people, from writers to technicians to actors, brought this fairy tale for adults to life. In an earlier episode, Mister Rogers spent a day with Margaret Hamilton, who starred as the Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz. After she explains her experience of acting as the witch, she takes the time to put on the old costume, and even lets out a cackle! It’s magical.

Rogers was never coy about how he created his own cast of imaginary friends, and how he drew inspiration from everyday events. He often brought in items from his past, such as his child-size piano. There was no pretense or posturing, just a frank discussion about the hard work that goes into creating stories from nothing.

Imagination Is a Tool to Develop, Not a Gift Handed Down

In 1996, Mister Rogers published a book of fan mail titled Dear Mister Rogers, Does It Ever Rain in Your Neighborhood? The opening chapter is devoted to answering the question he received the most from children: Are you real? His typical response is yes and no. But in his usual style, he congratulates the writer for wondering about it, and he recognizes how important it is for children to ask the kinds of questions that they may one day laugh about. Like, how does Mister Rogers fit inside the television? Can he climb out of it somehow? Can he see the people at home watching him?

Rogers often spoke about how his show established a clear delineation between the “real” world of his home and the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. And yet many young viewers still had trouble figuring it out—but Rogers knew that testing those limits was part of a longer process of exploration, one that lasted throughout a person’s life (if they’re living it right).t

Be Compassionate

In the real world, no one is totally evil nor purely good, and one of the great challenges of writing is showing how even villains deserve our empathy, and even heroes have flaws. Almost every episode of Mister Rogers did both.

One of his iconic songs, “It’s You I Like,” may seem like a cutesy piece about accepting people for who they are. But it contains a line that is surprisingly sophisticated and dark for a young audience:

…but it’s you I like.

The way you are right now,

The way down deep inside you,

Not the things that hide you…

Not the things that hide you. Even children (including childlike characters like Daniel Tiger) can create masks for themselves—mimicking the adults in their lives, I suppose. Recognizing that everyone does this at some point is part of growing up, and is an essential lesson in creating believable, relatable characters.

Mister Rogers took this need for understanding a step farther in the way he showed respect for fellow storytellers. Perhaps the most famous parody of his show is Eddie Murphy’s acerbic “Mister Robinson’s Neighborhood” sketch on Saturday Night Live, a recurring bit which began in 1981 and continued through the early ‘80s. Mister Rogers could have ignored it, or tut-tutted about it in the way so many celebrities tend to do when their brand is compromised. Instead, Mister Rogers chose to be gracious. When he visited NBC studios for an interview on a late night talk show, he took the opportunity to pay Murphy a surprise visit—a moment captured in one of the greatest Polaroids ever taken. For Rogers, reaching out and getting to know someone, even someone known for goofing on his work, was always worth the effort.

Don’t Worry About How Silly You Might Look

We should all hope to one day achieve a Mister Rogers-level of confidence when doing something we have never done before. From drawing to breakdancing, Mister Rogers’ principles never wavered: try something new whenever you can, and if you love it, keep working at it even if you fail.

In one of the most famous episodes, Mister Rogers visits Hall of Fame football player Lynn Swann at a dance studio, where Swann stays in shape by practicing ballet. Without an ounce of the machismo one might expect, Swann talks about how much he loves ballet, and of course Mister Rogers is nothing but impressed with the effort that goes into it. Whereas we might see an oddity, based on our preexisting assumptions, he saw passion that was worth celebrating.

Oh, the things we could do, the stories we could tell, if only we stopped worrying about what naysayers thought of us!

Kindness Is the Way of the Future, Not a Quaint Relic of the Past

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood premiered in 1963, one of the most difficult and divided years in modern American history. And yet, much like Star Trek, the show and its creator foresaw a world that could shed the petty differences holding society back. In some ways, this vision was expressed in subtle or casual ways; after all, the characters and guests were among the most inclusive at the time. But in other ways, it was more overt, like when Mister Rogers invited the friendly neighborhood police officer played by François Clemmons to dip his toes in his small backyard pool. The message was clear: an African-American man would share a formerly segregated space with Mister Rogers, and an entire generation of young people would see it as if it were a normal, everyday occurrence. And there would be no turning back.

Though I’ve enjoyed dystopian literature over the last couple of decades, I often wonder if we are nearing the tail end of that trend, with more optimistic stories on the horizon—stories that focus on what we could be, rather than wallowing in how bad we currently are. Perhaps this shift will require more than just mere fatigue at the grimness and pessimism of current narratives. Instead, it will require a new way of looking at things, more innocent and less fearful of what lies ahead. In his unique way, Mister Rogers helped lay the foundation for that new perspective, even if we weren’t quite old enough to notice at the time.

Originally published May 2018

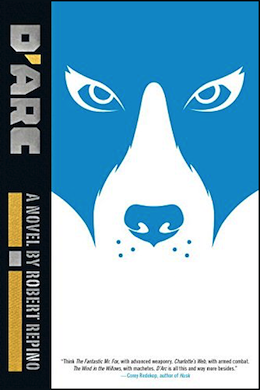

Robert Repino (@Repino1) grew up in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. He works as an editor for Oxford University Press and has taught for the Gotham Writers Workshop. He is the author of Mort(e) (Soho Press, 2015), Leap High Yahoo (Amazon Kindle Singles, 2015), Culdesac (Soho Press), and D’Arc—book three in the War With No Name series, now available from Soho Press.

Robert Repino (@Repino1) grew up in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. He works as an editor for Oxford University Press and has taught for the Gotham Writers Workshop. He is the author of Mort(e) (Soho Press, 2015), Leap High Yahoo (Amazon Kindle Singles, 2015), Culdesac (Soho Press), and D’Arc—book three in the War With No Name series, now available from Soho Press.